Before the Darkness

The summer light in Western Sydney used to look different to John Cobby. It had a gentle shimmer, the kind that lifted dust off the roads and laid it like lace across the rooftops. On weekends he and Anita would drive with the windows down, the radio low, the future wide open. She would reach for his hand at red lights, laughing at something small— a dog leaning out of a ute, a kid wobbling past on a new bicycle— and he would think: this is what peace feels like.

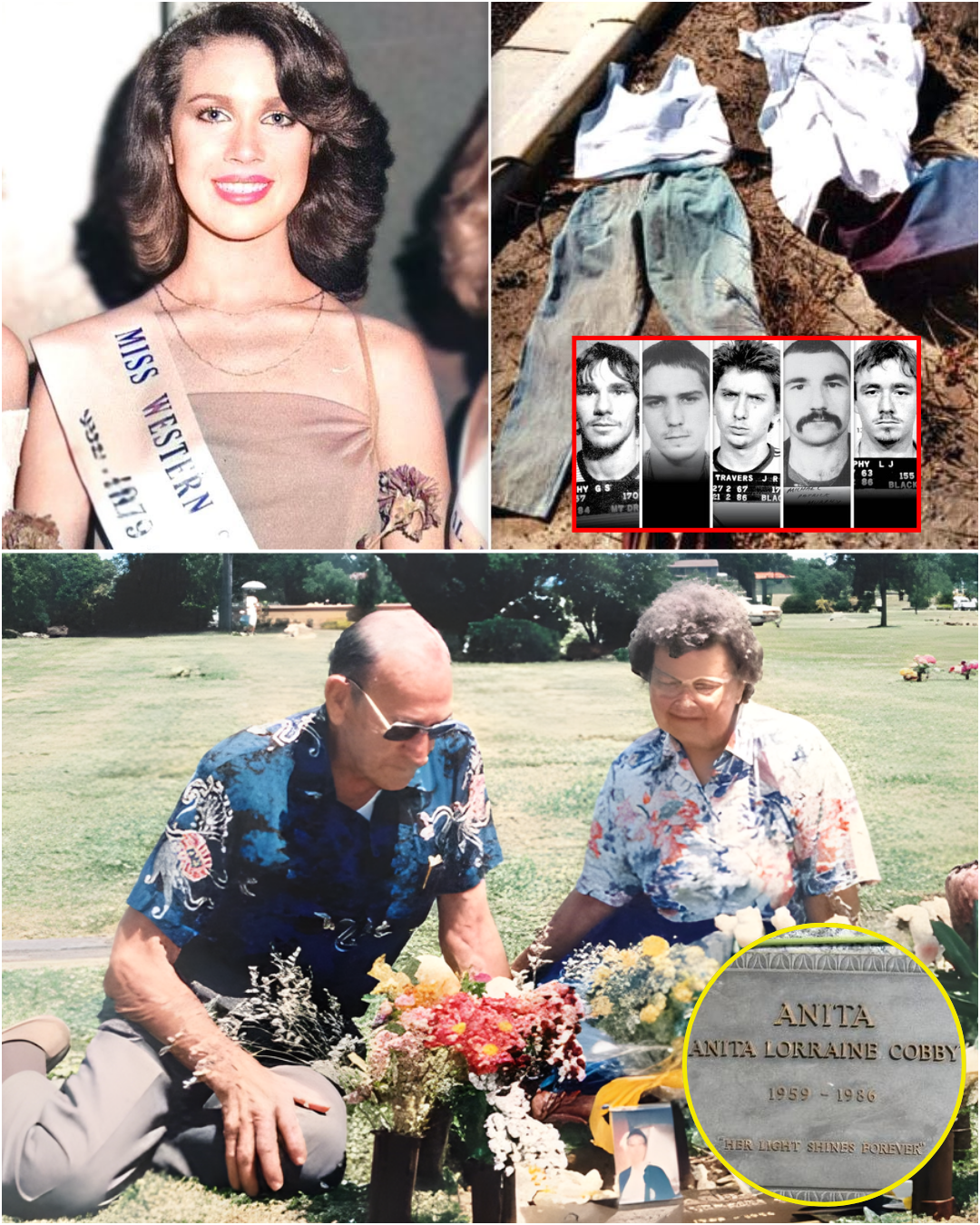

Anita Lorraine Cobby was twenty-six and looked like sunlight should have looked on everyone. People often led with her beauty—former pageant winner, bright smile, the sort of presence that made rooms feel taller—yet what stayed with those who truly knew her was steadiness. She listened longer than most. She worked the shifts nobody wanted. She kept promises. At Westmead Hospital, patients remembered her hands: warm, sure, unhurried even on the longest nights.

She could have chased the kinds of dreams people push on pretty girls—TV spots, magazine spreads, rooms where applause can sound like love. She chose nursing. “Because people matter,” she told a friend who asked why. “Because when you’re in pain, the only thing that helps is a person who sees you.”

In photographs from that last year, you can read two stories at once. One is the romance—Anita leaning into John at a picnic bench, faces wind-flushed and happy. The other is the horizon forming behind them, not yet ominous, only vague. Life had been good; it was also complicated. They had loved fast and hard, then bruised, then tried, as serious people do, to be kinder next time. Separation papers can feel like a verdict; for Anita and John, they felt like a chance to think.

They talked about houses. They talked about children and whether grief can sit next to hope without spilling it. They argued about the pace of settling down—his instinct to anchor, her longing to learn more, see more, be more. They were two decent people in a difficult season, trying to decide whether to row back toward shore or keep floating in the channel for a while longer.

On the evening before everything changed, Anita was not in a courtroom or a headline. She was with co-workers at a casual dinner after a long shift, the sort of ordinary human night that never makes the news. There were jokes about supervisors and new-graduate nerves, a glass of wine, a promise to trade recipes, that easy female shorthand of borrowed lipstick and shared phone chargers. She said her goodnights. She was punctual, almost famously so; she said she would be home.

Blacktown, then, was a patchwork—family barbecues and footy and church rosters, yes, but also the rougher seams of a city growing faster than its rules. Anita knew the commute. She knew the timetable. She knew exactly where to stand on the platform to be beneath the brightest light.

What happens next is a set of facts the country would come to know by heart. But facts alone, stripped of the quiet before them, can’t hold the weight of a person’s life. It matters that she cleaned her station before she left. It matters that she told a colleague, “Text me when you get home.” It matters that she believed, as most of us do, that routine is a kind of safety.

When Anita did not arrive, the first alarm was small and private. A friend’s call. A father’s check of the front window. A mother moving the curtain with two fingers, the night air cool against her cheek. Late happens. Trains fail. Batteries die. Parents learn to tell themselves these gentle lies before the harder ones can form.

By morning, the absence had edges. Calls stacked up in the unanswered queue. The hospital confirmed she hadn’t swapped shifts. The neighbor’s light—always on when she walked by after a late roster—had been off at an hour it was usually on. The family reached for what families reach for next: the police. In a station that had seen its share of domestic arguments and bar-fight contusions, a missing person report can feel like smoke—there, but not yet enough to sting the eyes.

Except this one did.

Detectives started where detectives start. With the last phone calls, the last text, the last person to say “goodnight.” They traced the train line. They asked after the public phones near the station. They learned the little things that turn a map into a story: which taxi stand stayed busy after the late run; which streetlights flickered; which back fence dogs barked at everyone and which ones only barked at the wrong ones.

The first tips were what tips usually are—mismatched, overheard, wish-it-had-been-useful. A white car. A shout. A face that might have been someone’s cousin if you squinted. A boy and his sister thought they saw a woman being pulled toward a vehicle and told an adult who told the police who wrote it down, and later someone would sit at a kitchen table and wonder if the world would have changed if they’d looked longer or run faster or yelled louder. People always wonder this, as if guilt is a tax we pay for being human.

By the time the news reached beyond Western Sydney—by the time cameras learned to spell her name—what the police knew and what the public felt were moving on two different clocks. The police needed the exact minute the doors opened on the 9:12. The public needed to know someone—anyone—would be held to account. Both needs were real; neither could speed the other up.

There are moments, in any city, when the day seems to tilt. On that day, it happened in a field, where a farmer noticed something wrong with the way the cattle gathered at a fence line, as if drawn by a silence too heavy for their gentle bodies to ignore. He called. Officers came. The scene they found is part of the national record now, a grief so large that even the most seasoned among them took a half step back.

This is where storytellers often lean into horror. This is where some writers reach for words to summon what can never be told. It is enough to say a bright life was stopped. It is enough to say that cruelty can be as ordinary as a car and a road and a group of men who chose evil when decency would have been as easy as continuing to drive.

The knock on the door at the Cobby house is the detail that will never leave John. Not the sound—knuckles on wood can take on a thousand meanings—but the moment after, when time separates into a before and an after and you step into the after because you must. He went because a man goes. He thought he would be strong enough because a man thinks that. In some versions he was. In the truest version he wasn’t, because love refuses to obey our performance notes.

The press felt the tremor and came running, as they do. “Tragedy.” “Horror.” “Outrage.” The words were correct; they were also too small. A neighborhood started leaving dinners to go cold. A nurse clipped an IV line with a hand that shook for the first time in a decade. Schoolchildren overheard fragments at the bakery and carried them like pebbles home in their pockets.

Police work after a crime like this is part science, part stubbornness, part prayer you pretend is procedure. They lifted what could be lifted. They walked angles that only experience teaches—where a car might slow, where footprints might survive the wind. They went back through petty theft reports and vandalism calls looking for names that kept showing up whether anyone wanted them to or not. And the names did appear, as names like that do—young men already known, the kind who had learned how to bare their teeth too early and discovered how often the world looks away.

Sydney woke each morning to headlines that grew sharper. Fathers who thought of themselves as patient men found themselves swearing in the car beneath their breath. Mothers took a new kind of inventory—keys, wallet, phone, rage—and then went about their days anyway, because they had to, because the laundry does not fold itself and fear cannot be allowed to win the long game.

What a country does in the weeks after a crime matters, maybe more than what it does on the day itself. Australia did what good nations do—reeled, argued, showed up. The calls to reinstate the ultimate punishment were loud; the rebukes, equally forceful. In between, there were quieter acts that mean more over time: casseroles that arrived without a knock; cards slid beneath a door; a police sergeant who stood a little longer on a front step and said nothing, because sometimes the kindest sentence is the one you choose not to speak.

In a newsroom, a producer made a choice he would later call righteous. In a family kitchen, someone called it cruel. It doesn’t matter which of them felt more certain. What matters is that information—the kind that should have belonged to a folder and a chain of custody—was said aloud. It galvanized a country; it complicated a case. Families will spend the rest of their lives deciding whether the trade was worth it.

By then the detectives had followed the white-car rumor down enough blind alleys to recognize the one that was finally a road. A stolen vehicle report. Names that connected to prior charges. The kind of boastfulness that tends to travel through suburbs faster than shame. Interviews began in rooms that smell of floor cleaner and old coffee. “Where were you.” “I didn’t do anything.” “We’re not asking what you did. We’re asking where you were.”

It is an old dance, older than any of the young men at those metal tables. One of them will think he’s smarter than the police. Another will hope he is invisible. A third will blurt a detail the officers never said out loud—the kind of mistake guilt makes when it is given caffeine and no place to lie down.

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. That is the work of Part Two: the narrowing of suspects, the weight of witnesses, the long nights where patience beats bravado. Before that, it matters to name what grief made of the people at the center.

John moved through those days like a man trying to walk underwater. Friends fed him because he forgot. He drank because he wanted quiet—first one, then another, then so many he could make it a whole hour without seeing her face as it is in the photograph on the mantel. It is easy to judge men who reach for bottles. It is harder, if you have ever loved anyone, to imagine what else he should have reached for instead.

Anita’s parents did what parents do when the world goes bad—they made order. They kept a tray by the door for the flood of cards and small roses. They opened them all, even the ones that should have been left sealed. They looked at their younger daughter, who had always been the brave one, and asked her to be brave once more. In the weeks to come they would discover a new vocation almost no one asks for: turning private devastation into public service.

Among the nurses at Westmead, the small griefs began to organize themselves into something larger. They started walking in pairs to their cars at night. They raised money without a formal committee. They learned, grimly, which reporters asked the least cruel versions of the necessary questions.

In living rooms across Australia, parents sat their children down and used words they didn’t want to use. “Don’t walk alone.” “Call me.” “I’m not trying to scare you; I’m trying to keep you here.” Teenagers rolled their eyes, the way teenagers must, and then texted anyway, the way love wins in tiny, unreported increments.

The day before the first arrest, the sky over Blacktown was a polished blue. No one can prove weather changes outcomes, but hope is a weather, too, and it had begun, in ways almost imperceptible, to shift. A neighbor remembered something he hadn’t thought important. A mechanic called about a white car he’d seen behind a panel shop. A young officer, who had not yet learned how to separate his heart from his work and maybe never would, stayed an extra hour with a statement that felt like a puzzle piece turned at last to the right angle.

When the cuffs finally clicked, they sounded like metal does—sharp, ugly, real. The young men were not monsters in any mythical sense. That’s the scariest part. They were only human, and they chose. A nation can endure almost anything except the idea that evil looks like the boys who live three streets over. We prefer masks; we get mirror glass.

If this were a story about punishment alone, we could end here and call it justice. But Anita was a nurse. She believed in aftercare. She believed in the work you do after the ambulance leaves. Part Two will follow the making of the case—the witnesses who stepped forward, the tape that turned whispers into evidence, the courtroom that learned how to listen. Part Three will follow what love made from ruin: a family’s vow, a country’s reforms, the stubborn hope Anita left behind in a profession built to hold pain the way a mother holds a child—gently, and for as long as it takes.

For now, remember her as she was before a road and a choice and a week that should never have happened. Remember the steady hands. Remember the laugh. Remember the way she looked for the bright parts, even on the long nights. That is the truest record we have.

The arrest, when it came, did not feel triumphant. It felt like air returning to a room that had been held shut for weeks. By then the detectives knew what the public only suspected: there had been a car; there had been more than one man; there had been a sequence of decisions so callous that the investigation had to move with the caution you reserve for brittle things—truth among them.

They started with the white sedan.

Stolen-vehicle reports live on the edges of every police database, skittering like leaves in a wind nobody remembers starting. A constable with a knack for finding the thread no one else sees pulled up the week’s list and circled a make and model that matched, almost to the scuff, the car described by a teenager who’d looked out his back window and seen something no teenager should. Primer-gray under a coat of neglect; a dent over the left tail light; a sound like a loose belt when accelerating. Small details, the kind that either clutter a timeline or unlock it. Here, they unlocked it.

The names tied to that report were familiar in the way names become familiar to stations that police the same neighborhoods year after year: a set of brothers whose rap sheets read like a curriculum of poor choices; a friend, younger, mouthier, eager to be someone in the only way he’d ever learned; and a ringleader of sorts—laugh too loud, eyes too flat, the kind of charisma that looks like confidence until you look again and realize it’s only hunger.

They did not kick down doors. Television has ruined the public’s expectations that way. They watched first. They learned routes. They learned who borrowed a cousin’s couch and who still called his mother on Thursdays. They learned which panel shop would turn a blind eye to the mix of paint that never quite matched; which petrol station clerk would remember a face because it was handsome, or dangerous, or both.

Then they began to invite people to rooms with walls the color of wet cardboard.

Interviews in those rooms are as much about silence as speech. A detective will ask a simple question and let the quiet lengthen until guilt grows itchy. The first young man came in with shoulders high, chin higher. He said his name like it was a dare. He said he didn’t know Anita, hadn’t been anywhere near the station, couldn’t have been, wouldn’t have been, didn’t even know which line the train ran on. A detective slid a form across the table—stolen-vehicle report, his signature rounding out the bottom like a boast. The chin dipped, almost imperceptibly. He asked for water. When it came, he drank too fast and wiped his mouth with the back of his hand the way a boy does when he believes no one saw him cry.

The second one tried to be a ghost. “Wasn’t there.” “Don’t know them.” “Can’t help.” He had practiced those sentences in a mirror; they sounded good in a mirror. They sounded flimsy in that room. When he left, the officers noted the bounce in his knee, the way he kept checking the door, not to flee but in hope—hope that someone would step in and save him from the version of himself he’d become.

The third made the mistake detectives bank on: innocence does not produce specifics; guilt does. Asked whether he owned a knife, he snapped, “I didn’t use it,” and both officers wrote, at the same time, the same three words: He just confessed.

What the public would later call a “break” was not a bolt of lightning. It was a woman who loved a man unworthy of the word and decided, at the edge of her own patience, to help the police hear what he only bragged about to her. In another life, on another night, she might have been a hero for something smaller—pulling a neighbor’s toddler from a backyard pool, performing CPR on a stranger in a coles queue. In this life, she clipped a wire beneath her blouse and walked into a conversation she’d had a hundred times, this time with the tape rolling.

We talk about courage as if it is loud. Often it is the quietest thing in the room.

He told her everything because men like that think stories make them kings. He told her about the car—how easy it was to pop the column, how quick the engine turned over once you knew the trick. He told her about the road—what they said, what she said, the profanity he used like punctuation to prove to himself he was the kind of person who didn’t flinch at suffering. He told her names too, his and others, the ricochet of blame already starting in his throat. He laughed in places, not because anything was funny but because shame, cornered, sometimes bares its teeth and pretends to be pride.

Later, when the tape was played in a room lined with binders, a detective who had been in this work a long time pressed his thumb against his eyelid until the sparks came, the way a man widens a river in his head to push a boat of grief across more quickly. He had daughters. He had learned how to keep the cases from coming home with him. This one could not be kept out. None of them tried, after that.

Evidence is not only words. It is fibers that do not belong where they are found. It is a smudge of primer on denim that threads the white car to the hand that pushed a door shut. It is the geography of a night: a petrol receipt stamped at a time no one would admit to; a witness who remembered a jacket because it had a rip, right shoulder, patch shaped like a shark. It is the square of fabric a man kept like a trophy, as if evil could be a souvenir. It is the maps of phone booths near the station, all out of order that night, each one a small failure in a chain that might have saved a life.

Once they had the names, the rest was patience. A warrant for one and then for the others. A knock made with the back of the hand, the one that doesn’t break fingers when a door opens too suddenly. The shuffle of feet, the thud of drawers. The phrase every house knows but no house believes it will ever hear: “Police. We have a warrant.”

Arrest looks, in photographs, like a single frame—wrist, steel, head bent beneath a doorframe. In the real time of it, there are always extra seconds. The ones where a mother says her son’s name and it sounds like the first day of kindergarten, not the last day of someone else’s future. The ones where a neighbor peers around a curtain and drops it again because curiosity has its own shame. The ones where a young man—who is not a monster in the way fairy tales mean the word—does the math and realizes he is about to be seen for what he is.

No one cheered in those streets. In another suburb someone would have. In Blacktown that week, there was only the sound of a garden hose left running somewhere—water hitting concrete, running toward a drain that could not drink enough to wash anything clean.

The news, when it came, did what news does: exploded outward, gathered too fast, hit wrong places first. A talk radio host whose name is lost to time now did a full hour on how evil is not born but made, as if philosophy could comfort parents. A tabloid whose front page thrives on fury tried, briefly, to make the girlfriend in the wire a villain for not coming earlier; the next day they ran a fundraiser for the family and called themselves fierce allies. The truth was this: a country wanted a way to be useful and found too many ways to be loud.

Inside the station, the detectives built a story that the court could hear.

Courts are not for catharsis. They are for proof. When a case is this terrible, people forget that. They want a judge to weep, a jury to shout, a prosecutor to announce the world has been put back where it belongs. That is not what they are for. A prosecutor’s gift is restraint. She will walk a jury across a narrow bridge, one plank at a time, and trust that grief will wait on the other side.

The brief in Regina v. the five young men was a stack thick enough to stop a door. It contained the tape, transcribed so the jurors would not be asked to carry the sound of his voice home with them. It contained photographs, carefully chosen, the ones that spoke without punishing the eye. It contained witness statements that matched down to the detail of a dog barking and then going quiet as the car turned a corner. It contained the lab reports and the receipt stubs and the map with the one route that fit all the times.

Defense counsel did what defense counsel must do in any country that calls itself good. They poked. They prodded. They suggested the tape could be brag. They asked whether the witness saw what he thought he saw in a dark window with a streetlight three houses down. They held up the chain of custody and tugged to see if any link gave. Two of them tried to sever their clients from the pack, a shabby kind of math—if he is worse, then my man is less so. One claimed simple mind, another claimed he’d been asleep in a cousin’s flat with a girl whose name he did not know but who would surely remember him if only someone could find her. The jury learned, over days, that cowardice comes in as many flavors as cruelty.

What the jury also learned, minute by minute, was what a community looks like when it decides to hold. The boy who first told police about the car—the one with the dent and the belt squeal—testified with a voice that broke in the middle and still did not quit. The farmer talked about cattle the way country men do, like friends; when he paused, the courtroom hallowed itself without a word. The mechanic put his grubby hand on a sworn Bible and said he’d seen the primer under the white because boys like those never finish a job proper. A nurse from Westmead sat in the gallery for as many days as her roster would allow and then traded her shift with someone else so she could sit a few more.

John came once. Then again. Then every day. There is a photograph you have seen if you have studied the case. He stands outside the building, eyes red, mouth set, a man who is still deciding whether his job is to endure or to rage and discovering that some days it is both. If you were there you would remember not the cameras but the people who turned their cameras away.

In the middle of it all, the parents carried themselves with the gravity of people who have learned the true meanings of words newspapers use lightly. Victim. Justice. Closure. They learned what every bereaved family learns if they live in the spotlight long enough: closure is a myth; justice is a process; the only true words left to you are the ones you say to each other in a kitchen at two a.m. when the dishes are finally done and there is no sound but your own breath. They did something else, too, which would matter as much as any verdict—they began to build the scaffolding for a future they could not imagine inhabiting yet. It would have a name and an address and a mission statement; it would have rooms where people could say the unsayable and not be asked to whisper. It would have Anita’s name on a plaque, and later a park would have her name, too, because cities need places to put their grief besides headlines.

The voices outside the courthouse—those who wanted penalties the nation had laid down a generation earlier—were loud and not without logic. People said, as people will, that some acts unmake the social contract and deserve a final answer. Others reminded them that nations do not prove they are civilized by how they treat the lovely but by how they treat the worst among them. Between those positions, the courthouse stood, and inside, the law did what it could do: it listened, it weighed, it spoke in sentences that had numbers instead of adjectives.

There was a day—close to the end—when the tape was played for the jury. The room went smaller, the way rooms do when sound is a storm you cannot step out of. The words were blunt, the bragging grotesque, the laughter a note the prosecutor did not have to explain. No one moved. When it stopped, the crown did not push. She looked at twelve citizens and said only, “You have what you need.”

They did.

Verdicts are not healing. They are scaffolds the living climb so they can begin the work of repair. The guilty verdicts, when they came, read like chords struck low on a piano. Each man stood and heard the words that would shape the rest of his life. Life sentences. No release. In a nation that had abolished the final punishment, this was the closest approximation the law could offer to a community that wanted the clock wound back to the minute before a train platform, before a white car, before the decision to be monstrous found five willing hosts.

Outside, a crowd that had grown from a few dozen to a few hundred over the days did not cheer. It did not boo. It did something rarer. It breathed, together, once. Then it went home to small kitchens and family rooms and began, in the ways that matter most, to make the world slightly safer for one another.

If the story stopped there, it would be like most true-crime podcasts: an arc of horror to identification to punishment, roll credits. Anita was a nurse. She would have hated a story that ends with what cannot be undone. Part Three is not a coda; it is the point. It will follow a husband trying to choose life over the bottle that pretends to be one. It will follow parents who refuse to hand their child’s name to the abyss without a fight. It will follow a city and then a country building rooms where grief can sit without being rushed and where other families—who never wanted to know the Cobby name because knowing it means knowing why—can learn to stand again.

There will be a bench with her name and a park with her name and a service that says to other mothers and fathers, we cannot make the night shorter, but we can sit with you until dawn. There will be, in the faces of the nurses who come after her, a steadiness that looks familiar, and not only at Westmead. There will be a boy—older now, a man—who will raise his own children with a rule that sounds small but is the seed of a civilization: we walk each other to the door.

In every city there are five shadows walking some street tonight, about to choose. The grace of Anita’s life is not that she met five shadows and was overpowered. It is that, because she lived the way she did and because a community refused to let the worst people write the last sentence, those shadows will find more lights turned on, more neighbors watching, more mothers waiting at the door with keys in hand and love in their throats, and maybe—maybe—a boy among them will choose to be better.

The courthouse steps emptied slowly. Grief doesn’t rush, even when justice has technically arrived. John stayed until the last journalist left, until the air cooled and the courthouse shadow reached the curb. Someone offered him a ride; he declined. He wanted the walk, the long stretch of road between what had been decided and what could never be repaired.

For months afterward, his nights came in fragments—half dreams of the life that might have continued, half rehearsals of the words he wished he had said to her the night before the world folded in. He drank too much and then stopped for a while and then started again, the way a man might try to swim back to shore only to realize the current does not care for courage.

His parents-in-law did not try to pull him back. They were building something of their own—a structure made from paperwork, grief, and stubborn hope. They called it Homicide Victims Support Group, though it would grow into more than a name. It began in a single borrowed office with two chairs, a phone that rang too often, and a kettle that never cooled. Strangers arrived—families who now understood the particular silence of a room where a loved one’s voice should be. They shared photographs, awkwardly at first, then stories, then the kind of laughter that comes not from joy but from recognition. The laughter stayed. So did the people.

A few years later, government funding followed, and with it came staff, counsellors, and the building of Grace’s Place, a center where children who had lost someone to violence could draw, talk, or sit in quiet if that was all they could manage. The walls were painted with bright colors Anita would have liked—turquoise, lemon, light coral. Each window faced sunlight. The official documents called it therapeutic intervention. The parents called it something to hold onto.

The press moved on, as it always does. The five men remained behind bars, where time grows heavy and shapeless. They fought, sulked, aged. One died of illness, another from the slow violence prison does to men who cannot be left alone with their own thoughts. Each headline announcing their decline felt like a small, unsatisfactory footnote to the story Australia had already written. The country didn’t need them anymore; it needed what had come from the space they left behind.

At Westmead Hospital, a scholarship appeared in Anita’s name. Every year, a new nurse received it—someone who had shown both compassion and grit, someone who stayed the extra hour, who learned the family names of patients, who refused to let cynicism replace empathy. On the night the first award was given, the chief of nursing said quietly, “She is still teaching us.” It was true.

John lived long enough to see the scholarship become an institution. He remarried, eventually, to a woman who understood that love after loss is not replacement but continuation. He had a son. The boy grew up hearing Anita’s name not as a tragedy but as a kind of moral compass. You don’t run from what’s right, his father would say. You stand still, even when it’s hard.

That phrase—stand still—worked its way into the cultural lexicon, the way certain phrases do when they belong equally to courage and grief. Teachers used it. Politicians borrowed it, sometimes clumsily. Activists stitched it onto placards. It became shorthand for refusing to let cruelty dictate the terms of a life.

The park in Blacktown came later. There is a small plaque near the path lined with jacarandas. It doesn’t mention what was done to her. It says only:

ANITA LORRAINE COBBY (1959–1986)

Nurse, daughter, friend. Her kindness endures.

Every spring, when the trees bloom purple, children chase each other beneath them. Parents sit on benches named for donors and lost loved ones. Joggers pass without reading the plaque, and that, too, is its own victory—because the park belongs to the living.

There is a temptation, in stories like this, to end with a neat ribbon of redemption. Life resists that. What remains is not closure but continuation. The families still visit the graves; the nurses still walk each other to the car at night; the parents of other victims still pick up the phone and find someone on the other end who understands. The pain doesn’t vanish; it integrates, becomes part of the country’s weather.

And sometimes, in the quiet corners of Sydney, someone will remember the nurse who smiled at patients even after twelve-hour shifts, the girl who won a beauty pageant and chose service instead of spotlight, the woman whose name now marks a park, a scholarship, and a promise: that decency will not go quietly.

Australia learned something in those years that no nation wants to learn—that evil can look ordinary, that systems can fail, that kindness must be defended as fiercely as innocence. But it also learned, because of her, that survival is a collective act. You cannot resurrect what was lost, but you can refuse to let it define what remains.

So when the sun sets over Blacktown and the last children leave the swings, the air still carries a trace of her—discipline, laughter, and the unshakable belief that even in the face of the worst, we can choose to be better.

Epilogue:

Some stories become folklore because of horror. Anita’s became one because of endurance. The five men are forgotten one by one. The nurse is not. Her name has turned into a gentle commandment whispered in classrooms, hospitals, and homes across the country:

Stand still. Be kind. Keep watch.

That is all the justice the living can give, and sometimes, it is enough.

News

JUST BRUTAL. In a devastating turn of events no one saw coming, Patrik Laine has suffered another HEARTBREAKING setback in his recovery. This unexpected complication has completely derailed his timeline, and sources are now whispering that his season—and potentially his career in Montreal—is in serious JEOPARDY.

Just when it seemed things couldn’t get any worse for Patrik Laine, another devastating blow has struck the Montreal Canadiens…

IT’S OFFICIAL. Martin St-Louis just made a SHOCKING lineup change, giving young phenom Ivan Demidov a massive promotion that will change EVERYTHING. This bold move signals a new era for the Canadiens’ offense and has sent a clear message that the youth movement has truly begun.

The wait is finally over. For weeks, Montreal Canadiens fans have been catching tantalizing glimpses of a significant shift on…

Martin St-Louis has delivered a ruthless and public message to Arber Xhekaj after his DISASTROUS game in Vancouver. His brutal benching is a clear sign that the coach’s patience has completely run out, leaving Xhekaj’s future with the Canadiens in serious JEOPARDY.

Martin St-Louis’s patience has finally run out, and he sent a message to Arber Xhekaj so loud and clear it…

Has Martin St-Louis finally had ENOUGH? His shocking new lineup decisions have sent a clear and brutal message to Arber Xhekaj, suggesting the enforcer’s time in Montreal could be over. Fans are in disbelief as this move hints that a trade is now IMMINENT.

A seismic shift is underway on the Montreal Canadiens’ blue line, and Martin St-Louis’s latest lineup decisions have sent a…

This is INSANE. A bombshell report has exposed the gargantuan contract demands for Mike Matheson, a deal that would make him one of the highest-paid defensemen in the league. Fans are in disbelief over the STAGGERING numbers, and it could force a franchise-altering decision: pay up or lose him FOREVER.

The Montreal Canadiens are facing a monumental decision that could define their defensive corps for years to come, and it…

CANADIENS’ $18 MILLION WAR CHEST EXPLODES INTO NHL CHAOS – SECRET MEGATRADE TO SNATCH A SUPERSTAR FRANCHISE KILLER FROM RIVALS IN A SHOCKING MIDNIGHT HEIST THAT WILL BURN THE LEAGUE TO THE GROUND AND CROWN MONTREAL THE NEW DYNASTY OVERNIGHT!

Jeff Gorton and Kent Hughes just flipped the NHL’s power grid upside down—without lifting a finger. While the hockey world…

End of content

No more pages to load