Daniel Martell Speaks… But Something Feels Off | Lily and Jack Sullivan

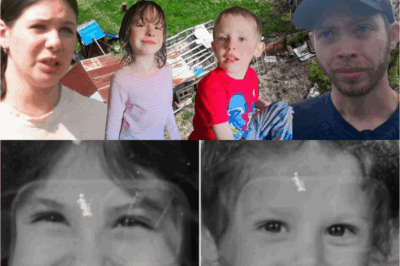

Six-year-old Lily Sullivan and her four-year-old brother Jack Sullivan are still missing in this rural area of northeastern Nova Scotia. The RCMP is the lead agency here, along with EHS. Hundreds of search and rescue crew members—from Halifax to Cape Breton—have been involved.

During the daytime, anywhere from 100 to 140 trained searchers comb the woods.

A spokesperson for the Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education confirmed the two children were students at Salt Springs Elementary School. Their stepfather told reporters they had both been out sick all week before disappearing on Friday.

The school has deployed additional support staff on-site at Salt Springs for anyone needing support.

Meanwhile, the search continues into the night here in the Lansdown area of Pictou County for young Jack and Lily Sullivan.

This is the case of Lily and Jack Sullivan: a mystery that has shaken a quiet community and baffled investigators. But sometimes, the answers aren’t hiding in the woods.

They’re hiding in plain sight.

Today, we’re taking a closer look at the man who stood before cameras and spoke for the missing: Daniel Martel, their stepfather. Because in the world of statement analysis, how you say something can matter more than what you say.

“I know they took their boots. That’s pink boots for Lily, blue boots for Jack—with dinosaurs on them. Lily had her backpack, white, with strawberries on it. I imagine now, after being in the woods, it would probably be brown. But I don’t see them carrying their backpack. I don’t see them keeping a pull-up on for that long after it got soaked from the very first day. We only found the two boot tracks outside the house—probably 10 feet away, in the backyard.”

At first glance, this sounds like the kind of detail you’d expect from a caring stepfather—specific, sensory, almost tender.

But in forensic linguistics, when someone starts with what they know—not what they think, not what they saw—we ask: how do you know?

Because here’s the truth: he never says he saw the kids leave with those boots. He doesn’t describe helping them put them on, or even seeing them at the door.

He simply asserts it as fact: “I know.”

That phrasing shifts his tone from witness to narrator.

And that’s important. Because when someone inserts knowledge they can’t confirm, we must ask: is that knowledge constructed or concealed?

Then, there’s the shift to Lily’s backpack:

“It was white with strawberries on it. I imagine now, if they’re in the woods, that it would be brown.”

Again, we get a vivid, picturesque image—emotionally resonant, yes—but what he’s doing here is subtle.

He’s pulling us into a mental simulation, not offering evidence. It’s not fact. It’s visualized speculation.

That’s a pattern we see in people trying to guide the narrative. The use of imagined conditions—dirty boots, soaked pull-ups, weather-worn backpacks—creates the illusion of knowledge while avoiding any real-time observation.

He’s not describing what he saw. He’s describing what he wants us to believe.

Then comes the most important line of all:

“We only found the two boot tracks outside of the house.”

Not: the kids walked away.

Not: we followed their trail.

Just: two boot tracks, ten feet from the house.

Because in real missing child cases, parents latch on to hope. They speculate wildly. They chase every possibility.

But here, Daniel Martel constructs a quiet, self-contained version of events—clean, linear, emotionally sterile.

The woods swallowed them.

And now, he paints scenes from inside that darkness.

But the real darkness might not be out there.

It might be here—in the words he chooses, and the truth he avoids.

“Now I urge you—probably to come out—if you have anything, come out as fast as possible and get it to any detachment or any police service that you have available to get to talk to…”

Jack loves bugs. Dinosaurs. Anything like that.

But Lily—Lily loved girly things.

But she also loved doing everything with Jack. Bugs.

They’re like best friends.

Not just brother and sister.

He looks straight into the camera. His voice is steady. His words sound rehearsed.

“…If you have anything, come out as fast as possible and get it to any detachment…”

Based on this short clip, he’s doing better than the children’s biological mother.

He’s asked for help.

He’s inconclusive about what happened—even though he heavily suggests they are in the woods.

But just seconds later, the narrative pivots:

“…Jack just absolutely loves bugs, dinosaurs. But Lily—Lily loved girly things.”

Did you catch it?

Past tense. Lily loved…

This isn’t just a grammatical slip.

In statement analysis, this is a red flag waving from the depths of subconscious disclosure.

Innocent parents almost always refer to their missing children in the present tense. Because without proof of death, the mind clings to hope.

Past tense implies resignation. Acceptance. Or in some cases… guilty knowledge.

It’s one of the most reliable linguistic indicators taught to law enforcement worldwide. And it’s not just theory—it’s been proven in case after case.

When a parent slips into the past tense prematurely, they’re often revealing what they know, not what they fear.

But there’s more.

Notice the tone. He doesn’t describe the urgency of the moment.

No panic, no chaos, no silence that must have filled the house when they realized Lily and Jack were gone.

Instead, we get strawberry backpacks, dinosaurs, and bug collections.

Comforting. Disarming. Almost too composed.

Because when people are in crisis, their language reflects that. Their breath shortens. Their thoughts fragment. Emotions bleed through words.

Here, we see the opposite:

A man who speaks not with pain, but with precision.

Does this mean Daniel Martel harmed the children?

No.

Does it mean he knows more than he’s saying?

Possibly.

But what it means—unquestionably—is this:

When you describe a missing child in the past tense before a body is found, you’ve already buried them in your mind.

“We were searching. We covered everywhere possible—even in the first day. Even with me running through the woods ahead of the helicopters, ahead of the drones, screaming as loud as I could until my throat hurt. Running through water that was up to my waist. As soon as I got back, I wasn’t allowed back in the woods until a man—dressed in military outfit—said I could go.”

Four days into the search for his missing stepchildren, Daniel Martel pleads with the public. But he’s begun to lose hope.

“If they are anywhere in the vicinity, they hate being wet and cold. They would have come right back into the house. The only two prints are right beside the house, facing the road. That’s it.”

He wants the search to extend to provincial borders. Maybe they were abducted.

“Post any officers they can get. PI border. NB border. Every airport possible.”

He confirms that when the kids disappeared from the home behind him, Lily was wearing a pink shirt and pink rain boots.

A man running through the woods, waist-deep in cold water. Throat raw from screaming. His stepchildren gone.

And with cameras rolling, Daniel Martel does what so many parents in crisis have done before:

He tells the story—of how he tried to bring them back.

“We covered everywhere. I was ahead of the helicopters. Ahead of the drones.”

It sounds heroic. Desperate.

But here’s where it gets interesting.

Because when people describe their actions in high-stakes moments, they usually center the outcome.

“I searched and found nothing.”

“I didn’t stop until they pulled me away.”

But Daniel?

He centers himself.

“Even with me running through the woods…”

“My throat hurt…”

“I wasn’t allowed back in…”

This is called spotlighting the self.

Placing emotional weight not on the missing children, but on the speaker’s experience.

It’s subtle—but powerful.

Because grief doesn’t narrate itself.

Guilt does.

Then, he adds a striking detail:

“…until a man in a military outfit said I could go.”

That evokes authority, restriction—but also plants a defense:

“I wasn’t allowed to do more.”

A rhetorical shield. Long before any accusation is made.

And again, he pivots:

“They hate being wet and cold. So they would’ve come right back.”

Would have.

He’s not speculating. He’s asserting.

And then—he says:

“The only two prints are right beside the house, facing the road. That’s it.”

News

HIDDEN EVIDENCE UNCOVERED! The DISTURBING Clues Police Are HIDING About The Sullivan Children That Will Make Your Blood Run COLD!

Anomalies experts have “noted” and an updated timeline of the Jack and Lilly Sullivan case.Hey y’all. I was looking for…

BREAKING: Children VANISH Without A Trace! What Police AREN’T Telling You About The Sullivan Kids Mystery Will TERRIFY Every Parent!

Hey guys, I want to give a quick update on this weekend’s searches for missing six-year-old Lily and four-year-old Jack…

TERRIFYING: Children VANISH Into Thin Air! Police Hiding What They REALLY Found in the Woods? The Chilling Day 14 Update No One Is Talking About!

It’s been two weeks since two young children vanished without a trace in rural Nova Scotia. Here’s everything we know…

STEP-DAD’S SILENCE SPEAKS VOLUMES! “CONFESSION TAPE” LEAKS As Police RUSH To HIDDEN LOCATION! Sources Say Sullivan Children Were ALIVE YESTERDAY — WHAT COPS DON’T WANT YOU TO KNOW!

NEW SEARCH for Lilly & Jack Sullivan: Do cops have new info? Confession? Step-dad says no comment we’re continuing the coverage…

SHOCKING DNA FOUND! Sullivan Children’s Clothing PROVES Who TOOK THEM! Police DESPERATELY Hiding The TRUTH About These “INNOCENT” Items — FAMILY IN TEARS After Discovery!

FOLLOW UP on ITEMS FOUND during Search for Lilly and Jack Sullivan!Today, we’re going to be talking about little Lily…

EX-COP BREAKS SILENCE: “The PARENTS KNOW WHAT HAPPENED!” BOMBSHELL Evidence in Sullivan Children Case POLICE DON’T WANT YOU TO SEE! “Family Member Did It” – FORMER DETECTIVE REVEALS ALL!

“Everybody is a suspect” in the disappearance of Lilly & Jack Sullivan says ex homicide detective it’s a very sunny Friday…

End of content

No more pages to load